ICAL's end of year wrap up

The end of the year is approaching, and it's been a very successful autumn for ICAL, with papers and prizes during a very busy term. Below is an update.

The closing months of 2016 have proved a busy but successful period for ICAL. Three papers have appeared:

Brasier, M.D., Norman, D.B., Liu, A.G., Cotton, L.J., Hiscocks, J.E.H., Garwood, R.J., Antcliffe, J.B., and Wacey, D. 2016. Remarkable preservation of brain tissues in an Early Cretaceous iguanodontian dinosaur. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 448: SP448.3. doi: 10.1144/SP448.3.

Hickman-Lewis, K., Garwood, R.J., Withers, P.J., and Wacey, D. 2016. X-ray microtomography as a tool for investigating the petrological context of Precambrian cellular remains. Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 448: SP448.11. doi: 10.1144/SP448.11.

Wacey, D., Battison, L., Garwood, R.J., Hickman-Lewis, K., and Brasier, M.D. 2016. Advanced analytical techniques for studying the morphology and chemistry of Proterozoic microfossils. Geological Society, London, Special Publications,: SP448.4. doi: 10.1144/SP448.4.

Of these, the first received significant press coverage - its findings are highlighted by a press release from the University of Manchester, listed below. In addition to these papers, a number of ICAL members have just returned from the 60th Annual Palaeontological Association Conference in Lyon, France. Here ICAL member Dr Rob Sansom was recognised with the Hodson Award for contributions to palaeontology by an early career researcher. Over the course of the conference, Dr Joe Keating, and PDRA in the centre, won the President's Award for best talk, and PhD student Emma Randle presented a poster which was highly commended, as well as winning a small grant to support her research into bite marks in palaeozoic fish.

Press release

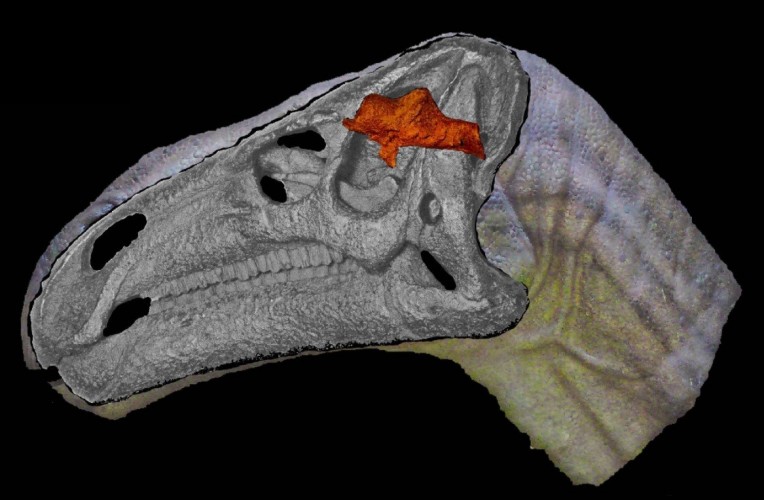

An unassuming brown pebble, found more than a decade ago by a fossil hunter in Sussex, has been confirmed by researchers from The University of Manchester and the University of Cambridge as the first example of fossilised brain tissue from a dinosaur.

The fossil is most likely from a species closely related to Iguanodon - a large herbivorous dinosaur that lived during the Early Cretaceous Period about 133 million years ago – and displays distinct similarities to the brains of modern-day crocodiles and birds. The results are reported in a Special Publication of the Geological Society of London, published in tribute to Professor Martin Brasier of the University of Oxford, who died in 2014.

Finding fossilised soft tissue, especially brain tissue, is very rare, which makes understanding the evolutionary history of such tissue difficult. According to the researchers, the reason this particular piece of brain tissue has been so well-preserved is that the dinosaur’s brain was essentially ‘pickled’ in a highly acidic and low-oxygen body of water – similar to a bog or swamp – shortly after its death. This allowed the soft tissues to become mineralised before they decayed away completely, so that they could be preserved.

The researchers used scanning electron microscope (SEM) techniques in order to identify the tough membranes, or meninges, that surrounded the brain itself, as well as strands of collagen and blood vessels. Structures that could represent tissues from the brain cortex also appear to be present. The structure of the fossilised brain, and in particular that of the meninges, shows similarities with the brains of modern-day descendants of dinosaurs, namely birds and crocodiles.

In typical reptiles, the brain has the shape of a sausage, surrounded by a dense region of blood vessels and thin-walled vascular chambers (sinuses) that serve as a blood drainage system. The brain itself only takes up about half of the space within the cranial cavity.

In contrast, the tissue in the fossilised brain appears to have been pressed directly against the skull, raising the possibility that some dinosaurs had large brains - however, the researchers caution against drawing conclusions about dinosaur intelligence, as it is most likely that the brain of this dinosaur collapsed and became pressed against the bony roof of the cavity as it decayed.

Quotes ICAL team memmber Russell Garwood: "This is a really interesting specimen, and by CT-scanning it we've managed to get a clearer picture of which parts have preserved tissues, and which are mostly sediment infill. Untangling the complex history of how this might have come to be preserved was something of a challenging, and working as part of a global team has allowed us to use a number of different approaches to study the fossil. Professor Brasier was a very supportive colleague, and it's been a privilege to work towards publishing a paper on this very special object, in a book in his memory."

More information: Guardian, BBC Today Programme, New York, Times, Telegraph, NPR, The Times, National Geographic, Vox, CBC, Reuters, IFLS, The Conversation.